Wild and Woody

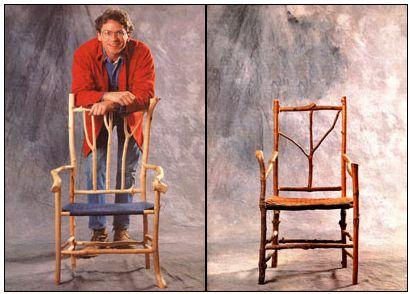

Twig furniture blends the growing tree with the personality of the builder.

By Daniel Mack. Mother Earth News, no.103 (January/February 1987).

I capture the power of saplings. . . and want some chairs to dance.

As the tree grows, so the chair goes. That's the almost magical transformation that accounts, at least in part, for the increasing popularity of rustic furniture-chairs, sofas, even beds made from full saplings or branches, often with the bark left on. For the city dweller, such furniture carries with it a touch of nature. For those in the country, it's yet another gift from the nearby forest. And for those who like handwork, making these functional sculptures can turn into a challenging and rewarding craft.

I make my living designing and building rustic furniture. Occasionally I teach others to do so and have yet to find a student who can't create a satisfying object. It is a truly democratic craft, both primitive and immediate. As such, it doesn't really have as much to do with sticks and twigs as it does with the people who put them together.

The main roots of rustic furniture making in America reach to the so-called Romantic Movement that flourished in the nineteenth century and was marked by the attitude that contact with nature had a soothing, spiritually healing effect. Summering in the mountains was seen as the clear antidote for the debilitating, relentless, confusing stress of ur ban industrial living. As a result, the "Great Camps" of the Adirondacks and the various resorts and retreats in the Smokies, Appalachians, and Catskills sprang up. Their architecture and furnishings reflected the romantic notion of intimacy with nature. More practically, however, the use of native building materials kept building costs down while also employing local craftspeople. Finally, both builders and users found something immensely pleasing in this crude but beautiful furniture.

Making Rustic Furniture

Many of these characteristics contribute to the appeal of creating contemporary rustic furniture today. There's true excitement in finding, cutting, and drying just the right piece of wood. There's also a delightful bewilderment in the many choices the rustic furniture builder faces in design, assembly, and finishing.

You make what you are. Because simple rustic furniture can be built with a minimum of formal woodworking skill, it could be said to be a translucent and sometimes transparent window into its maker. Every workshop I teach reaffirms this. The selection of woods, and the arrangement, the assembly, and even the intended use of a rustic chair tells more about the person who made it than it does about trees or furniture. A rigid person is likely to produce a straight conventional piece, while a more flexible one will explore the possibilities of wood shapes more freely.

When making my own furniture, I try to capture the power of saplings that have fought the good fight-battling for light and nutrients; surviving frost, gypsy moths, lightning, browsing deer, and Boy Scouts. I want that forest epic, which is written all over the bark, to be able to be read by the people who see my furniture.

Secondly, I want to bring humor and illusion to my work. I want some chairs to dance, others to look like they're about to be reclaimed by the forest. Many tweak the nose of high-style furniture by sporting Queen Anne legs and Windsor backs-all formed by natural growth rather than by the lathes of the royal carpenter.

Finally, I strive to instill a quiet grace and beauty in my work-a chair or bed is an opportunity to marvel at the airy curves and exploding forks made by the trees. I want to set this 'beauty apart from the forest and celebrate it. That's what I try to do and-just sometimes-it happens. With the information that follows, you can pursue the same rewarding, if elusive, ends.

Choosing Wood

Use wood that's available. Cut it yourself, and talk to local tree surgeons, developers, or the highway department. Because I sell my rustic furniture, I prefer to cut live hardwood saplings so I can avoid the insect and fungal damage that generally afflicts fallen wood.

Pick wood with character. Look for interesting bends and unusual bark patterns. Such embellishments make for a more intriguing finished piece but require a more complicated process. It's a tradeoff: Certainly the easiest furniture to make is from the straightest pieces, but it can also be the least exciting to view.

Think about the scale of the work. Probably the single distinguishing characteristic among rustic furniture makers is the difference in the scale of designs and the proportion of woods each uses. The relationship between the size of upright posts and the horizontal rails is, to my mind, an essential deter minant of beauty in the finished piece.

Use dry wood. For a first effort, you might try dead standing or even fallen trees. As a rule, however, you'll want to get green wood. Once you have done so, size it roughly into rungs, posts, etc., and then let it air-dry indoors a minimum of three months. Dry rungs sound like drumsticks when knocked together. (It's less important that the posts or uprights be bone-dry.) To minimize the drying time, try to cut wood in the winter months when the sap is down. This also minimizes the chances of the bark falling off.

Planning Rustic Furniture

To get started, I suggest you copy or interpret a favorite piece of conventional furniture. Take a kitchen chair to the woods or the woodpile and find twig twins for all the parts. Interesting choices and changes will soon present themselves. You'll find yourself developing opinions and preferences. In short, your own "style" will begin to emerge.

"I'll tolerate anything in my chairs that's not a hazard to my body."

Making a rustic chair that is also comfortable, however, can be like asking a bear to dance. There's a possibility it will happen, but an extremely remote one. It's probably wiser, at least at first, to put comfort toward the bottom of your list of priorities. I'll tolerate anything in my chairs that is visually pleasing and not an obvious hazard to my body. In planning your creation, for instance, try to make sure that the back slants backward and that the back decoration and support structures don't protrude into the sitting part of the chair. Plan to put a comfortable seat in later, or simply use pillows. But also think of all the other uses of a chair: for looking at, for throwing clothes on, for newspapers, magazines, and sleeping cats. If these functions don't make sense to you, don't make a chair. Try a rustic table or ladder instead-objects in which comfort plays only a small role.

Getting It Together

There are a variety of ways to put rustic furniture together, depending on the skills of the maker, the use of the piece of furniture, the tools available, and the wetness of the wood.

Mortise-and-tenon joinery is peg-in-hole joinery. I use 5/8"-diameter tenons that are 3/4" long. I've cut hundreds of tenons with my pocketknife, but I presently use an antique tenon cutter, the hollow auger, which fits on the end of my hand brace. You could use a hatchet, a lathe, or a saw to score the depth of the tenon, a chisel or knife to chip away the excess, and a rasp to round it off.

I now cut mortises with a spur bit on my drill press. Before that I used a hand power drill with a similar bit, and I know many makers who prefer to use a hand brace and bit.

Among the problems with rustic mortise-and-tenon joinery is the shrinkage of the tenon in the mortise and the subsequent loosening of the joint. If both members are dry, this rarely occurs. But there are two ways to get around this potential problem. One avoids it; the other attempts to work with it. The first is the blind dowel tenon. Mortises are drilled both in the post and in the end of the rung. A single length of kiln-dried hardwood dowel is then fitted and glued into each pair of mortises, and the joint is established. The tenon won't shrink, though there is a chance the mortise might crack around the dry tenon.

The second method is the "wet joint." Here tenons are cut on the rungs, and care is taken to make sure the tenons are drier than the wood of the mortised piece. When the piece is assembled, the tenon will absorb moisture from the mortised wood and will swell. When all the wood finally stabilizes, the mortise will have neatly shrunk around the tenon, more than the tenon itself may have shrunk. No glue is used, and a firmly woven seat provides the final insurance for a tightly constructed chair.

If you have doubts about the strength of a mortise-and-tenon joint, try putting a peg or even a nail through the joint. (If you use a peg, make sure it is no more than one-half the size of the diameter of the tenon itself.)

Another common form of rustic joinery is the nailed joint. After two pieces have been put together or slightly notched, they are nailed in place. The trick to an enduring nailed joint is this: Predrill the hole for the nail in both members, making it just a bit narrower and a bit longer than the nail. Within a few months, a nailed joint will shrink, exposing the nailhead and perhaps a bit of the shank. At this time, give the nail a final knock to drive it farther into the predrilled hole.

When I nail a piece, I use ringed nails, cement-coated nails, or any grooved nail; when the wood shrinks it bites and locks around the grooves for a strong joint.

Finishing the Piece

All indoor rustic furniture needs some kind of treatment to make it look like a finished creation rather than a random collection of sticks. Also, a finish helps preserve the uneasy truce between the bark and the wood beneath it. Dry bark is more brittle than dry wood and needs care. I first sand the bark gently to lighten the final color and, perhaps, to highlight certain features of the piece. I then apply a generous coat of raw linseed oil cut with a bit of turpentine. In a few days I apply another coat and let it dry well. After that, I'll use furniture polish or more linseed oil as needed to maintain a matte, leatherlike finish. Personally, I don't like the glossy urethane look on rustic work.

The final challenge of rustic chair making is the seat. And I must admit that I have yet to find the perfect solution. I've used nicely grained planks, split saplings, and full, round twigs; I've woven seats from leather strips, split oak, and ash and hickory bark. I've even tried upholstering with old quilts, new hightech fabrics, and a weave of twisted rags. For the moment I make my seats from a woven cotton strapping that comes in a variety of colors.

Solving the often exasperating seating problem is the last aesthetic statement the builder can add to the finished work. But, when all is said and done, the ultimate delight of rustic furniture lies simply in living with it, in finding ways to use it, and in watching it slowly and gracefully age.

How I Got Started

One day at an antique auction in the country, I bought a rustic child's chair for my daughter. Later, at home in the city, I decided to copy it,choosing for the summer project maple, a wood I immediately fell in love with. After making several chairs I was proud of, I attempted to interest a retailer in merchandising them. Emboldened by my workshop success, I was nevertheless shy about representing these pieces as my own. After all, I was-so I thought-an overeducated urban dweller, hardly the model of a rural craftsman. So I told the buyer that the small chairs had been made by an old man who lived by himself in the woods upstate somewhere, and that I was only his agent. The buyer balked, not because of the credibility (or lack thereof ) of my story, but rather because he wasn't interested in children's chairs particularly. "Why don't you see if that old man has any adult chairs," he said.

"Then come back."

Well, adult chairs are a world apart from children's chairs. You can't just scale them up. Dynamics, proportions, structural tension-all are entirely different, as I quickly discovered. I didn't make it back until many months later, after I had begun to master the technique of working on a larger scale. Meanwhile, I had become thoroughly hooked on making rustic furniture of all kinds. The shopkeeper bought the adult chairs and also learned their true origin. Since then, I've given up my career as a television producer and college journalism teacher, and I now earn my living making rustic furniture full-time. My chairs sell for more than $600 each, couches and settees for twice that, and beds for as much as $2,200 each. I still love maple and search for it and other interesting trees in the woods two or three times a month. Occasionally I take my daughter with me on these treks, but she deplores my single-mindedness. "Dad," she asked me not long ago, "why can't you just walk in the woods like other people do?"